After all the ballots were counted in the recent Canadian federal election, was anyone surprised that Gudie Hutchings, incumbent Liberal MP in the district of Long Range Mountains, Newfoundland and Labrador, had been re-elected?

After all, western Newfoundland has been a Liberal stronghold since the days of Joey Smallwood. Nevertheless, Hutchings has become something of an endangered species: a rural Liberal MP.

In 2021, the Liberal caucus was thoroughly urban, its members drawn by the dozen from Canada’s largest cities. By land area, fully 87 per cent of ridings the Liberals won in 2021 could fit comfortably within the borders of Hutchings’ Switzerland-sized constituency.

Urban/rural concentration

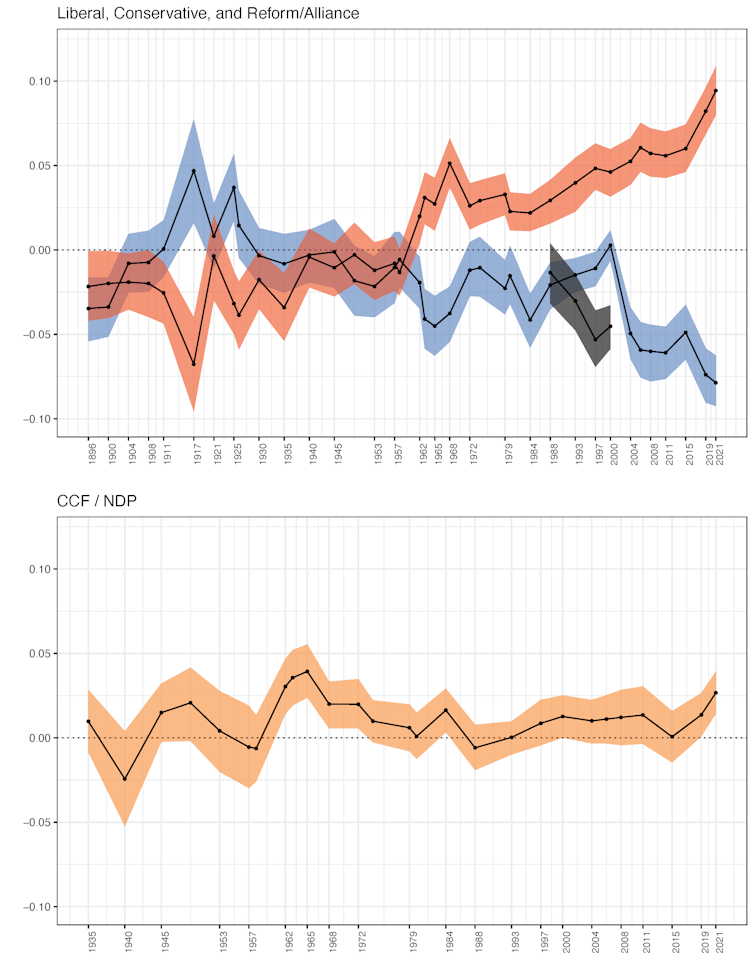

In a paper soon to be published in the Canadian Journal of Political Science, we investigate how support for the major political parties has been concentrated in urban or rural areas through time. Our first step was to develop a way to consistently score each of Canada’s more than 4,000 historical federal electoral districts on an urban-rural scale. We then use this new measure to explore when the major parties developed urban or rural vote-share advantages.

(Jack Lucas and Zack Taylor)

What did we find? A steadily widening urban-rural divide in support for the Liberals and Conservatives since the early 1990s.

A longer historical view shows that while smaller gaps emerged between the two parties in the 1920s and again in the 1960s and ’70s, the urban-rural gap between the two parties was greater in the 2019 and 2021 elections than at any point in Canada’s history.

After the Progressive Conservatives joined with the Canadian Alliance in 2003, the new Conservative Party inherited the Reform-Alliance rural base. Aside from 2011, when the Conservative Party picked up more urban seats around the greater Toronto area, the divide only expanded.

The Liberals, not the NDP, are the urban party

Think of the New Democratic Party today, and you may conjure an image of a “downtowner” party rooted in the latte and laptop crowd. But this image is incorrect: the NDP has never been a distinctively urban party in Canada.

This is because the party has continuously held seats in rural resource industry communities in places like northern Ontario and the B.C. Interior, balancing out its seats in large urban centres. In fact, NDP support was most urban in the distant days of the early 1960s, when its seats were concentrated in labour-friendly communities in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Hamilton and Toronto.

The Liberal party, not the NDP, is Canada’s unequivocally urban party, and it has been for a long time.

In short, our research shows that the urban-rural divide in support for Canada’s major parties has been around for generations, but has dramatically intensified over the past 25 years. The urban-rural divide predicts election outcomes more strongly today than at any previous point in our history.

This is worrisome for several reasons. As parties become durably uncompetitive on each others’ turf, they lose touch with the concerns of significant portions of the population. Recruitment of talented candidates who are connected to local communities becomes more difficult.

The portion of each party’s caucus that comes from safe seats increases. As the parties increasingly represent different social and economic worlds and speak different policy languages, conflicts will only become more entrenched.

American-style polarization ahead?

While the causes of urban-rural polarization are likely different south of the border, the United States’ highly conflict-ridden politics represent a possible future for Canada.

On the other hand, history shows that change is possible. After decades of Liberal dominance, John Diefenbaker assembled a new majority coalition of Conservative supporters in 1958 that differed from before. He combined rural Prairie ridings that had previously supported the Progressive Conservative and Social Credit parties and rural Québec ridings that traditionally voted Liberal with new urban support in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto and Montréal.

Brian Mulroney did the same in 1984. And not so long ago, Stephen Harper and Jack Layton managed to temporarily disrupt the trend toward the urban-rural polarization we identify — Harper pushed into urban regions while Layton had surprising victories in rural Québec.

Disadvantaged parties always have an incentive to reconfigure the playing field by creatively building unanticipated coalitions. But the leader who succeeds in disrupting the status quo must overcome a powerful long-term trend in the other direction.![]()

Zack Taylor, Associate Professor of Political Science, Western University and Jack Lucas, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.